The Progress Foundation has now been in existence for 7 years and we have given or committed grants of nearly £1 million. This seems like a good time to reflect on whether we have achieved what we set out to do – help young people reconnect with society. We have been working on some metrics which illustrate what we have done, but first of all we reflect on some of the research which has emerged in recent years.

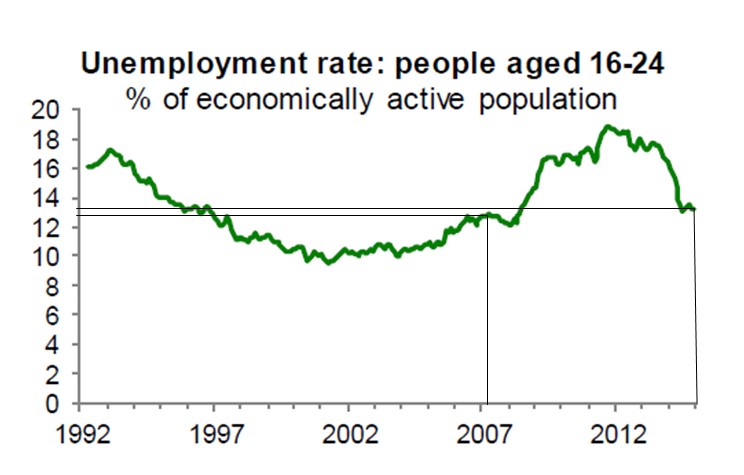

This seven year period coincides, of course, with one of the deepest recessions in recent economic history and for much of that time young people took the brunt by finding it harder to get work. Employment levels in the UK have stayed remarkably high during the recession, but this has largely been the effect of those already in the workforce retaining their places, while those aged 16-24 have had higher levels of unemployment. Nonetheless, youth unemployment rates have now gone down to the same level as before the recession

Source: Underlying graph is from the House of Commons Library Standard Note SN/EP/05871 18 March 2015. The horizontal and vertical lines have been added to highlight the period of Progress Foundation operation

These lower levels of unemployment do not mean that the issue has gone away – 13% is still high and those who have had long periods of unemployment may suffer a longer term drag on their career prospects.

We are not only worried about employment levels – research has also shown that higher levels of academic achievement can provide a substantial boost to well-being, health and prospects for the next generation as well as employment prospects. This means we care about whether young people leave school with qualifications, progress to further education and have a sense that they can contribute to society.

As well as learning from our experience of giving grants, our approach has been informed by a number of interesting books on education and the life prospects of young people. For those who may be interested they are described below and, for those with the time, are well worth a read:

Progressively Worse by Robert Peal (https://goodbyemisterhunter.wordpress.com/about/) argues that literacy levels in our young people have barely changed despite record levels of spending on their education. He points the finger squarely at progressive educational techniques based on the premise that young people “are both innately good and natural learners, who should be freed from the guidance and direct instruction of the teacher”. He goes on to argue that this approach has effectively lowered teachers’ expectations of young people from poorer areas, thus condemning them to a poorer education.

Daisy Christodolou (https://thewingtoheaven.wordpress.com/about/) echoes Robert’s findings in her Seven Myths about Education. She too critiques current pedagogic approaches and says that children deserve to be taught facts and subject content rather than just skills – without them, they are lacking the context in which to apply the skills.

Paul Tough’s How Children Succeed (http://www.paultough.com/the-books/how-children-succeed/) argues that what matters most in determining young people’s future is “skills like perseverance, curiosity, conscientiousness, optimism, and self-control.”

A thought provoking programme from “This American Life” about the different educational outcomes for two cohorts of young people who attended schools just three miles apart (http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/550/three-miles) has also influenced our thinking. Those from poorer backgrounds often make it to further education but, unlike their more privileged contemporaries, they rarely graduate. The reasons seem to echo Paul Tough’s findings that grit is important, but also include pervasively low levels of self-esteem and lack of social capital (links to informal networks of people who can support and advise these young people and who know their way around further education and the jobs market).

Finally, Robert Putnam’s new book Our Kids (http://robertdputnam.com/) brings much of this research together in a study of why social mobility from the poorest classes in society has reduced so much. His work is, of course, based on the US experience which differs in many important ways from the UK. One of his recommendations, for instance, is for a financial safety net for the poorest families which already exists to a much greater extent in the UK. He also looks at ways of preventing teenage pregnancies, but these are now at a record low in the UK (see here), so this is less of a factor here. Other conclusions, however, have great significance for the UK which has even lower levels of social mobility. Much of the difference in outcomes for the top and bottom quartiles in society relate to the durability of marriages of parents with degrees, parenting styles and parental investment of time and money. He also cites differences in social capital, with better off kids having much more access to valuable informal mentoring. One big difference between the UK and the US is in the levels of such informal mentoring for all classes which comes from organised religion – as a much more secular society these links are less available here. He also points to research which shows that extracurricular activities have enormous value in teaching young people to work together, giving them self-confidence and providing them access to caring adults. Middle class parents, of course, recognise this, which is why they invest so much in these activities; poorer parents and poorer schools cannot hope to match this investment.

So what do we learn from all this:

- Self confidence matters and our young people seem to be lacking the self-esteem which generates self confidence. We should expect more of all our young people and make them believe that they can achieve more at school and in life.

- Middle class parenting styles work – and we need to try to extend the benefits to those who don’t have parents doing this hard work on their behalf

Mentoring can make a huge difference – Putnam says that “mentoring can help at-risk kids to develop healthy relations with adults….and to achieve significant gains in academic and psycho social outcomes.” - Extracurricular activities (sport, music, debating, clubs) have a positive effect and needs to be supplemented for those attending schools where provision is poor. Young people also need to learn important stuff – to read, facts and real skills.

None of these findings would be valid without good evidence – this can be really hard to come by in the world of social change but charities are, rightly, getting better about thinking about this. In a future blog entry, we will examine the extent to which those organisations we have supported help address some of these areas.